| |

dicembre |

Paolo Canettieri, Vittorio Loreto, Marta Rovetta, Giovanna SantiniHIGHER CRITICISM AND INFORMATION THEORY |

Data d'immissione: Dicembre 2005 |

Philology is a human science primarily applied to literary texts and traditionally divided into lower and higher criticism. Lower criticism tries to reconstruct the author's original text and higher criticism is the study of the authorship, style, and provenance of texts. The employment of methods borrowed from information theory makes it possible to bring together methodologically some of the sectors of the two fields. The outcome of the experiments in both text criticism and text attribution has been encouraging. In the former, the tests performed on three different traditions have provided results very similar to those obtained by traditional methods in a great amount of time (Canettieri et al. 2005). The experiments carried out both at the levels of 13th century Italian poets and schools have shown that it is possible to draw texts closer to one another. Furthermore, the method we have used allows establishing the attribution of anonymous writings: in particular, the attribution of the poem Il Fiore to Dante Alighieri is probably to be excluded in favour of his master Brunetto Latini.

Within the frame of attribution there is generally a distinction between ‘external’ and ‘internal’ criteria (Contini, 1984). The former concern the witnesses of other authors, as well as historical, cultural or biographical references in the text, and analysis of the sources. On the other hand, the ‘internal’ criteria are those that the philologist can draw from direct analysis of the language, of the metre or style of a text. The latter criteria are those followed by stylometry, which is the quantitative and statistical analysis of the literary style. For this type of analysis to be applied profitably it is necessary that the texts compared are sufficiently long and that they can be compared from the point of view of genre, language and contents. Furthermore, the stylistic aspects under consideration will have to respond to the requisites specified by Bailey in 1979, i.e. they will need to be outstanding, structural, frequent, easy-to-quantify and relatively free from the conscious control of the author. The methodological proposals that have so far followed one another vary essentially in the choice of the characteristics to be used as units of measure of the style: they vary from average length of words (Mendenhall 1887; Brinegar 1963; Mosteller, Wallace 1964), to average number of syllables per word and frequency of monosyllables (Fucks 1952; Fucks, Lauter 1965; Bruno, 1974; Brainerd, 1974), to length of sentences (Yule, 1938; Williams, 1940; Wake, 1957; Morton, 1965; Sichel, 1974; Kjetsaa, 1979). The stylistic traits which have been considered pertinent are the percentages of the different parts of discourse (nouns, verbs, adjectives, etc.) used in a text (Somers, 1966; Antosch, 1969; Brainerd, 1973 and 1974), the frequency of the so-called ‘function words’, i.e. the words that are not determined by the context (Ellegard, 1962), as well as the preference assigned by the author to either of the elements of a pair of synonyms (Mosteller, Wallace, 1964; Morton, 1978; Burrows, 1987). Up until now, stylistic investigations have generally been of the lexical type: statistical models have been developed to calculate the richness of an author’s vocabulary, the average distance in which new words are generated in a text, the percentage of presence of hapax legomena and hapax dislegomena (Holmes, 1994). Finally, great emphasis has been given in France to the controversy aroused by the method of measurement of ‘intertextual distance’ proposed by Labbé and Labbé (2001). The two scholars performed complete lemmatization of the texts to be examined and then analyzed the distance between the dictionaries obtained: the shorter the distance, the greater the likelihood that the two texts could be assigned to the same author, or belonged to the same literary genre, or had been written in the same period or were dealing with the same subject.

We'll now present a short and oversimplified summary of our information-theory oriented approach. For a more formal treatment we refer to Benedetto et al., 2002, 2003 and Baronchelli et al., 2005. Born in the context of electric communications, information theory has acquired, since the seminal paper of Shannon (1948), a leading role in many other fields as computer science, cryptography, biology and physics (Zurek, 1990).

In information theory the word information acquires a very precise meaning, namely that of the so-called entropy of the string, a measure of the surprise the source emitting the sequences can reserve to us. Suppose the surprise one feels upon learning that an event E has occurred depends only on the probability of E. If the event occurs with probability 1 (sure!) our surprise in its occurring will be zero. On the other hand if the probability of occurrence of the event E is quite small our surprise will be proportionally large.

One could now ask how is it possible to extend the definition of the entropy for a generic string of character without any reference to its source. This is the typical case when one has a text written for which the source or its statistical properties could be typically unknown. Among the many equivalent definitions of entropy the best for this case is the so-called Chaitin – Kolmogorov complexity or algorithmic complexity: the algorithmic complexity of a string of characters is given by the length (in bits) of the smallest program which produces as output the string. A string is said complex if its complexity is proportional to its length. This definition is really abstract, in particular it is impossible, even in principle, to find such a program. Since this definition tells nothing about the time the best program should take to reproduce the sequence, one can never be sure that somewhere else it does not exist another shorter program that will eventually produce the string as output in a larger (eventually infinite) time (Shannon, 1948; Khinchin, 1957).

One has to recall now that there are algorithms explicitly conceived to approach the theoretical limit of the optimal coding. These are the file compressors or zippers. It is then intuitive that a typical zipper, besides trying to reduce the space occupied on a memory storage device, can be considered as an entropy meter. Better will be the compression algorithm, closer will be the length of the zipped file to the minimal entropic limit and better will be the estimate of the entropy provided by the zipper. It is indeed well known that compression algorithms provide a powerful tool for the measure of the entropy and more in general for the estimation of more sophisticated measures of complexity.

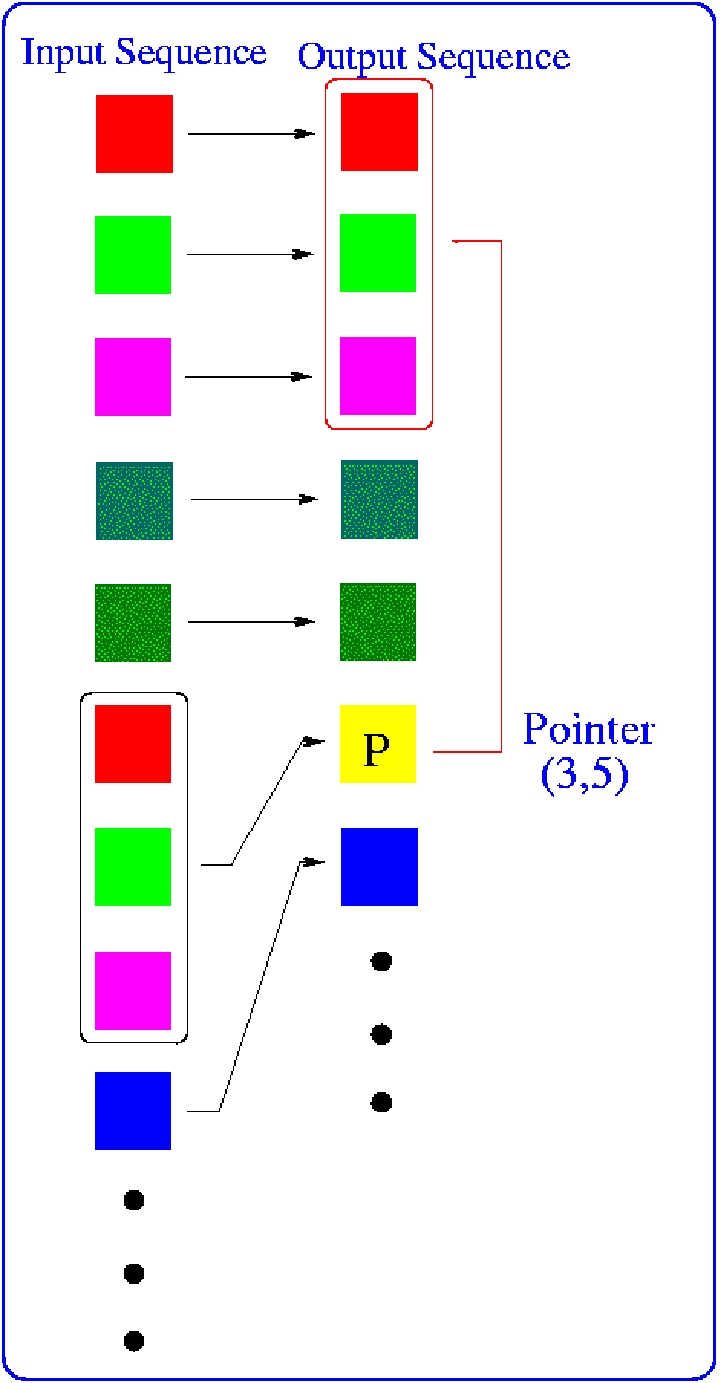

A great improvement in the field of data compression has been represented by the so-called LZ77 algorithm (Lempel, Ziv, 1977). This algorithm zips a file by exploiting the existence of repeated sub-sequences of characters in it. Its compression efficiency becomes optimal as the length of the file goes to infinity (Wyner, Ziv, 1994). It is interesting to briefly recall how it works. The LZ77 algorithm finds duplicated strings in the input data. The second occurrence of a string is replaced by a pointer to the previous string given by two numbers: a distance, representing how far back into the window the sequence starts, and a length, representing the number of characters for which the sequence is identical. For example, in the compression of an English text, an occurrence of the sequence the will be represented by the pair (d,3), where d is the distance between the occurrences we are considering and the previous one. It is important to mention as the zipper does not recognize the word the as a dictionary word but only as a specific sequence of characters without any reference to the words belonging to a specific dictionary. The sequence will be then encoded with a number of bits necessary to encode d and 3. Roughly speaking the average distance between two consecutive the in an English text is of the order of 10 characters. Therefore the sequence the will be encoded with less then 1 byte instead of 3 bytes.

Figure 1. The LZ77 algorithm searches in the look-ahead buffer for the longest substring (in this case substring of colors) already occurred and replaces it with a pointer represented by two numbers: of the matching length and distance.

It is interesting to recall the notion of relative entropy (or Kullback-Leibler divergence: Cover, Thomas, 1991) which is a measure of the statistical remoteness between two distributions. A linguistic example will help to clarify the situation: transmitting an Italian text with a Morse code optimized for English will result in the need of transmitting an extra number of bits with respect to another coding optimized for Italian: the difference is a measure of the relative entropy between, in this case, Italian and English (supposing the two texts are each one archetypal representations of their Language, which is not).

We should remark that the relative entropy is not a distance (metric) in the mathematical sense: it is neither symmetric, nor does it satisfy the triangle inequality. For our purpose it is crucial to define a true metric that measures the actual distance between sequences. Our proposal is based on the computation of the relative entropy. There exist several ways to measure the relative entropy. One possibility is of course to follow the recipe described in the previous example: using the optimal coding for a given source to encode the messages of another source.

Here we follow the approach recently proposed (Benedetto et al., 2002), which is similar to the approach by Merhav and Ziv (1993). The aim is that of defining a notion of remoteness between two text, from now on identified as A and B, exploiting the properties of the relative entropy. In particular we start reading sequentially file B and search in the look-ahead buffer of B for the longest sub-sequence already occurred only in the A part. This means that we do not allow for searching matches inside B itself. As in the usual LZ77, every matching found is substituted with a pointer indicating where, in A, the matching subsequence appears and its length. This method allows us to measure (or at least to estimate) the cross-entropy between B and A, and consequently their relative entropy.

Now we address the problem of defining a distance between two generic sequences A and B. A distance D is an application that must satisfy three requirements: positivity, symmetry and triangular inequality. As it is evident the relative entropy does not satisfy the last two properties while it is never negative. Nevertheless, in order to obtain a real mathematical distance one can define a symmetric quantity by using the symmetrized relative entropy which can be made satisfying the triangular inequality with a suitable prescription (see Baronchelli et al., 2005 for details). It is important to quote that there exist similar approaches to define a distance between pairs of sequences (Otu and Sayood, 2003, Li et al., 2004, Kaltchenko, 2004).

Starting from the distance matrix one can construct a tree representation of the corpus. Our method is mutuated by the phylogenetic analysis of biological sequences (Cavalli-Sforza and Edwards, 1967, Felsenstein, 1984) and takes as input the distance matrix, i.e. a matrix whose elements are the distances between pairs of texts (sequences) and produces as output a tree whose leaves are the elements of the corpus. With these trees a classification is achieved by observing clusters that are supposed to be formed by similar elements.

The classification power of the method we have adopted can be verified on corpora related to the works of a specific period. The system has proven efficient for the classification of texts according to hierarchical criteria: in particular, it can bring closer texts belonging to the same author, associate different authors according to the poetry school, genre or socio-cultural milieu they belong to. The method has been applied to the texts of 13th century Italian poetry, also including in the corpus Dante Alighieri’s Divina Commedia.

All the editors’ interventions were removed from the corpus of texts that we used, and graphical rendering of metric and phonetic phenomena were standardized, respecting however the linguistic identity of the documents. All divisions, modern numbering of the texts, punctuation, integrations and emendations marks made by the critical editors have been eliminated. In order to facilitate the identification of equivalent lemmas, it was decided that phonosyntactic gemination should not be represented graphically, and that whenever possible synalepha was to replace the phenomena of apocope, apheresis, or elision not envisioned by contemporary Italian. All the electronic texts were subdivided automatically into files 10,000 characters long (i.e. a size of 10Kb), in order to have several texts for each work to be used for consistency and robustness checks. Texts shorter than 10Kb were left untouched. With the corpus of electronic ready we performed several experiments aimed both at the authorship attribution and to the construction of a classification tree of authors and schools. Texts were analyzed with the data-compression technique introduced in Benedetto et al. (2002) which allows to construct a distance matrix, i.e. a symmetrical matrix whose elements represent the distance between a pair of texts (for further details concerning the notion of distance and its definition we refer to Baronchelli et al., 2005). The distance matrix is then used in the framework of well-established phylogenetic methods to construct trees. Here we only present a synthesis of the results and we invite the interested reader to contact the authors for a more complete picture.

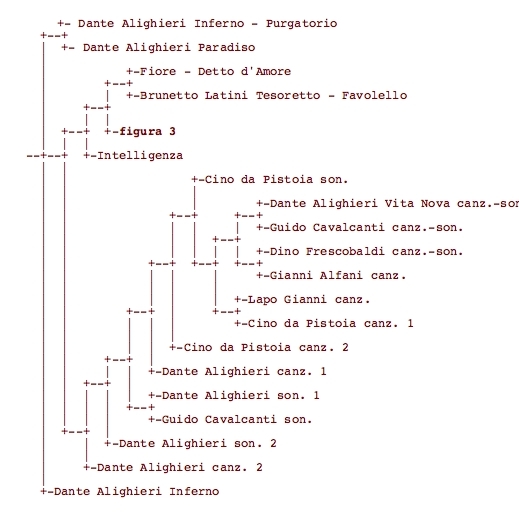

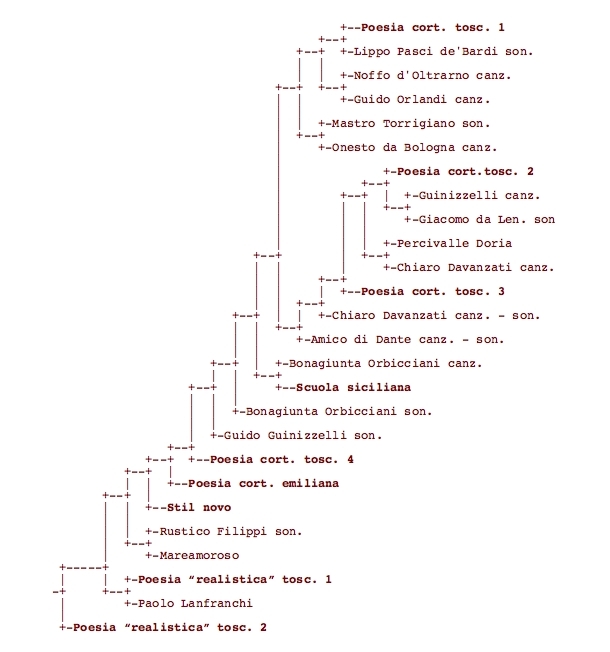

The groupings represented by the trees we obtained are generally consistent with those traditionally indicated in literary compendia (figg. 2-3). The program recognizes the poetry schools very clearly, and brings together the works of great as well as those of minor and less productive authors. The tree identifies the Sicilian School, the Dolce Stil Novo and the Tuscan courtly poetry. In the group represented by the poets of the Dolce Stil Novo, all the poems of the Vita Nova are connected by the same node, which is linked to that of Guido Cavalcanti’s works (fig. 3). The Commedia is collocated in a different branch separated from the lyrical production (fig. 2).

Figure 2. Summarized and simplified phylogenetic tree of the poetry works of 13th century (the length of the branches does not represent the distances): Dante Alighieri Inferno = 17 files; Dante Alighieri Purgatorio = 17 f.; Dante Alighieri Paradiso = 17 f.; Fiore = 12 f.; Detto d’Amore = 2 f.; Brunetto Latini Favolello = 1 f.; Brunetto Latini Tesoretto = 7 f.; Intelligenza = 10 f.; Cino da Pistoia son. = 1 f.; Dante Alighieri Vita Nova canz. - son. = 4 f.; Guido Cavalcanti canz. - son. = 3 f.; Dino Frescobaldi canz. - son. = 2 f.; Gianni Alfani canz. = 1 f.; Lapo Gianni canz. = 2 f.; Cino da Pistoia canz. 1 = 2 f.; Cino da Pistoia canz. 2 = 2 f.; Dante Alighieri canz. 1 = 2 f.; Dante Alighieri son. 1 = 1 f.; Guido Cavalcanti son. = 1 f.; Dante Alighieri son. 2 = 1 f.; Dante Alighieri canz. 2 = 2 f.

Figure 3. Detail of a branch of the phylogenetic tree illustrated on fig. 2: Poesia cort. tosc. 1 = Panuccio dal Bagno canz. - son. (4 files) and Dante da Maiano canz. - son. (5 f.); Poesia cort. tosc. 2 = Carnino Ghiberti, Bondie Dietaiuti, Neri de' Visdomini, Maestro Francesco, Inghilfredi da Lucca (2 f.), Bonagiunta Orbicciani canz. (2 f.), Pucciandone Martelli; Poesia cort. tosc. 3 = Chiaro Davanzati canz. - son. (8 f.), Rustico Filippi, Noffo Bonaguidi, Guittone d'Arezzo son.; Poesia cort. tosc. 4 = Guittone d'Arezzo canz. - son. (24 f.), Bacciarone di messer Baccone, Meo Abbracciavacca, Monte Andrea canz. - son. (11 f.), Jacopo da Leona; Scuola siciliana = Re Enzo, Stefano Protonotaro, Pier delle Vigne, Rinaldo d'Aquino, Federico, Ruggieri d'Amici, Giacomino Pugliese (2 f.), Ruggierone da Palermo, Tommaso di Sasso, Giacomo da Lentini canz. (3 f.), Mazzeo di Ricco, Jacopo Mostacci, Guido delle Colonne; Poesia cort. emiliana = Tommaso da Faenza and Onesto da Bologna; Stil novo = Guido Orlandi, Dino Compagni; Poesia “realistica tosc.” 1 = Cecco Angiolieri son. (6 f.), Meo dei Tolomei (2 f.); Poesia “realistica tosc.” 2 = Cenne da la Chitarra, Folgore da San Gimignano (2 f.), Muscia da Siena, Cecco Angiolieri son. dubbi (2 f.). Moreover: Chiaro Davanzati caz. - son. = 6 f.; Amico di Dante canz. - son. = 3 f.; Rustico Filippi son. (2 f.); Mareamoroso (2 f.); when the file number is not specified it means that there’s only 1 file.

Furthermore, the program provides precious suggestions for the attribution of anonymous works. In the case of works belonging to a known author, since the percentage of unidentification of files containing texts by the same author (procedure of identification “known author over known author”) is equal to 10%, this will be the percentage of unreliability for the cases in which anonymous works are drawn closer to works written by known authors. Therefore, the proximity of the Mare Amoroso to the production of Rustico Filippi is extremely interesting. Mare amoroso is the first example of poem in blank verse belonging to the Italian poetic tradition; the text, anonymous, is referred by one manuscript only, which also transmits the Tesoretto and the Favolello by Brunetto Latini. The first editor (Grion 1868) of the poem, just like its discoverer Trucchi (1846), ascribed the work to Brunetto Latini, essentially due to the presence in the codex of the two poems by ser Brunetto and to a number of recurring stylistic traits in the Mare amoroso and in the canzone by Brunetto S’eo son distretto. This hypothesis, supported by Bertoni (1901), was rejected by Gaspary (1882), Monaci (1912) and Cian (1901). Two more recent editors, Contini (1960) and Vuolo (1962), owing to the fact that the only witness could be dated back no later than to the beginning of the 14th century, agree on assigning the text to the end of the 13th century, without expressing themselves on the name of the author. The Florentine linguistic traits were confirmed by Gorni (1986), who supported the hypothesis of the Florentine provenance with some metrical comments about the origins of blank verse; finally De Laude (1993) again brought up the name of Brunetto Latini after careful analysis of the sources common to Mare amoroso, Tresor and Rettorica. Although unable to make any authorship proposal, we wish to underline that none of the elements so far ascertained, i.e. 13th century dating and Florentine traits of the author, hinder the vicinity that our tree establishes between the anonymous poem and Rustico Filippi, Florentine author of rhymes to whom Brunetto Latini dedicated the Favolello.

The most important result is represented by the position in the tree of the poem Il Fiore: it is strictly related to the Detto d’Amore, its homologue transmitted by the same manuscript, and linked to the node from which the work of Brunetto Latini also derives, while it is considerably distant from the production of Dante Alighieri. Il Fiore, a total of 232 sonnets representing in concise form the narrative part of the Roman de la Rose, had been attributed to Dante by its first editor Castets (1881) and this attribution, for a long time strongly contested, has then become largely approved thanks to the intervention of Contini who, starting from the contribution of La questione del Fiore (1965), up to the edition of the poem (1984), strongly supported Dante’s authorship. Contini was to inaugurate a new way of facing the problem of attribution, not based on external criteria, but on the stylistic analysis of the text and on a close comparison between the style of the author of the Fiore and that of the works certainly belonging to Dante. The quantity and quality of the matches induced Contini to consider them not as “una semplice somma di indizi, ma […] un organismo mnemonico […] del tutto assimilabile alla memoria che il Dante della Commedia ha di se stesso” (Contini, 1976). After years of almost unanimous consent to Contini’s thesis, scientific literature has recently raised again the problem of the poem’s authorship; in particular, Fasani (1998) reconsidered the hypothesis of ascribing the poem to Brunetto (already in Muner 1968-69 and 1970-71).

The association deriving from our method thus confirms the hypothesis of attribution by that part of scientific literature that assigns Il Fiore to Brunetto Latini. Furthermore, since Il Fiore is considered a translation of the Roman de la Rose, written in ancient French, Brunetto Latini would seem to be a valid candidate, since his most important work, the Tresor, is written in this language.

The reason for the good performance of the assignment method of the texts is of a linguistic type, in particular as regards lexicon and morphology. In the majority of cases the dictionaries of strings common to two texts, automatically produced by the software, indicate that the shared graphical sequences are linguistically meaningful: very often, entire lemmas (even in sequence) and especially suffixes and prefixes are involved. An approximate calculation indicates that the segments linguistically insignificant amount to just over 10%. Therefore, the single authors would seem to repeat the same words in uniform manner and to use similar percentages of occurrences of the same grammatical elements.

The trees thus allow to organize in taxonomic form the material available, generally confirming the main achievements of scientific literature, but also adding important concise information about the collocation of certain works. The method, from the identification of common strings upwards, can obviously also be applied in the field of intertextuality, making it possible for a single procedure to be applied to the most important fields of philology.

Further developments can be envisioned: on the one hand, as already said, the modes of analysis and classification of the manuscript sources will be improved, using the Lachmann method, on the other hand general information about diachronic distribution of the branches and nodes will be provided, eventually producing a single tree that includes both manuscript tradition and works. Other traditions could also be investigated, ranging from the many sectors of lyric poetry to the many forms of novel or stage prose, to the many anonymous or practical texts to be organised in a general taxonomy. Finally, other disciplines will be able to benefit from the same method, for example all historical and legal disciplines, and in general all those fields in which taxonomic study of the sources and acknowledgement of authorship of the documents are to be considered of primary importance.

References